Hiring the best tech talent: Purpose, Product, and Compensation

We live in a very peculiar time in history in which the demand for tech skills are so high that companies are going above and beyond to convince talent to join their mission. These are primarily software engineers, but also designers, product managers, managers, etc. As a tech person, I can tell you that without metaphors and analogies we wouldn’t be able to communicate. So I’m borrowing a well-known software paradigm to explain another, the project management triangle of scope, cost & schedule to explain how tech companies can excel recruiting talent.

Scope, cost & schedule*

Just in case you aren’t familiar with the trifecta of project management, it postulates that you can only have two out of the three attributes: scope, cost & schedule. In other words, you have to sacrifice one of the dimension to fulfill the other two. Are you sacrificing scope, cost (resources) or the schedule? Well, it’s a little bit more complicated than that, but you get the gist.

Purpose, Product & Compensation

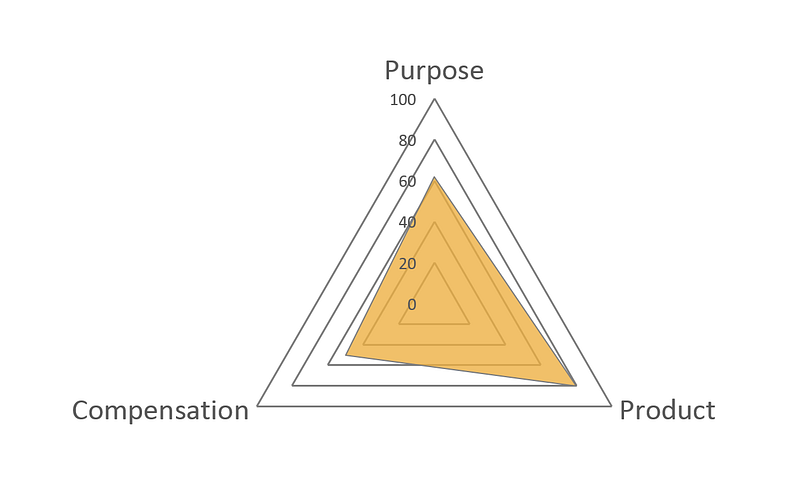

My theory of hiring great talent is that you need two out of these three: Purpose, Product & Compensation. If you have only one, you’re going to get substandard talent if you have all three you’re not optimized for the opportunity. The right number is two.

Let’s start by purpose. This has been well covered in the book Drive by Daniel Pink. People are incredibly motivated by the impact they are having in this world or in other people’s life. If you have a mission that people can rally behind it, you are in luck because you can have a stingy product or poor salaries (but not both), and people would still be knocking on your door.

Product is more than what the product does. Yes, it includes that too. But it’s also the underlying technology, tools, processes and the team building it. Top tech talent loves working with other smart people. They love the latest and greatest methodologies and tools. They love to learn new things. If your company can’t offer that, you’ll have to offset it with a very strong mission or with a big check.

Compensation is a tricky one because it’s the one thing you don’t really control as much if compared to your mission (“why”) and your product (“what”). The market (industry, location, technology) is the yardstick for compensation. If you have an incredible mission and an amazing team building an amazing product with the greatest technology, you probably can afford a below average package.

On the other hand, if you are building a website using 1995 technology to help people smoke more cigarettes, you might need to offer a sky-high salary to convince a top talent to join your company, or compromise and get the one person that can’t find a job because he’s utterly incompetent.

It’s not black-and-white

Here is the reality: purpose, product, and compensation have a spectrum and they are not a simple yes/no answer. You can have a purpose that goes from world-impacting life-saving (+100) all the way down to world-destroying life-killing (-100). Most startups are in the middle. As much as they believe what they are doing is very special, it’s just about an “average purpose.” Since there is very little in the extremes of the purpose scale, the nuances are important.

Given two ad-tech companies — and let be honest, they aren’t solving world hunger — the nuance becomes on who they are trying to serve and why. If one’s primary purpose is to help big brands sell more of their product, it might not sound as meaningful as another one trying to help small business all across the world compete in the same footing as their bigger counterpart.

One way to visualize this is this radar plot and your goal is to find the compensation (assuming you already have a mission and product in place) that maximizes this area so it’s just bigger than the other companies competing for the same talent.

Things Change

And one thing you have to keep in mind is that things change. The product changes, the mission might change and, for sure, the industry changes so your compensation package needs to be re-evaluated every once in a while. If you don’t pay attention to the change, you start getting bad attrition and difficulty hiring new employees even though it used to be easier.

(*For the astute reader, you know my initial analogy is not perfect, but, oh well.)